Building of the Month - June 2014

Blacksod Point Lighthouse, FALLMORE Td., County Mayo

A brief history of Blacksod Point Lighthouse, a familiar landmark on the tip of the Mullet Peninsula in County Mayo, and its role in the D-Day Landings

A brief history of Blacksod Point Lighthouse, a familiar landmark on the tip of the Mullet Peninsula in County Mayo, and its role in the D-Day Landings

County Mayo boasts a collection of lighthouses along its coastline. Safe entry to official harbours and ports was essential for the economy of the county and the Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin, established in 1786 and also known as the Ballast Board, was responsible for the construction of the lighthouses. The earliest lighthouse, on Clare Island, was first exhibited in 1806 but, following a fire, was replaced in 1818. The parish of Kilmore-Erris, in the north-west of the county, boasts four lighthouses, three of which – Black Rock (1858-62); Broadhaven or Ballyglass (1853-5); and Eagle Island (1836) – are attributable to George Halpin Senior (1776-1854), Inspector of Works and Lighthouses, or his son George Halpin Junior (1804-69). Each is characterised as a whitewashed tapering tower with a lantern encircled by serpentine railings on a corbelled walkway.

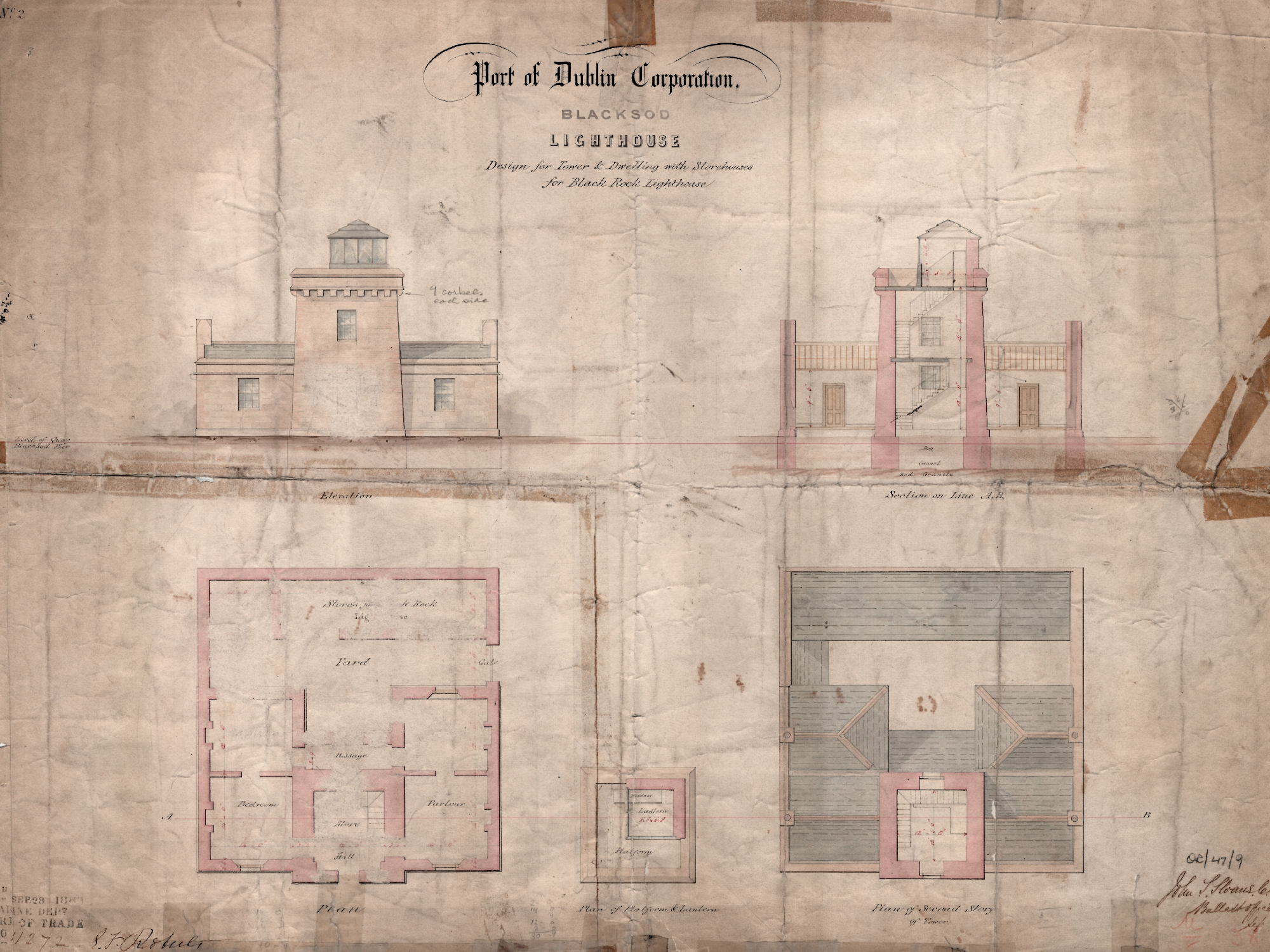

A lighthouse on the tip of the Mullet Peninsula was first mooted in 1841 when a request was submitted by Lieutenant John Nugent, Inspecting Commander stationed at Belmullet Coastguard Station, for a lighthouse on Black Rock. The request, forwarded to the Ballast Board by Admiral (Sir) James Dombrain (1793-1871), Inspector General of the Irish Coast Guard, was evaluated by Halpin Senior whose assessment was that a lighthouse on Black Rock would be useful to lead vessels into Blacksod Bay only with an additional light on Blacksod Point. No progress was made until a further request for a lighthouse on Black Rock was submitted to the Ballast Board in 1857; no mention was made of a lighthouse on Blacksod Point.

Further recommendations for a lighthouse on Blacksod Point were made by the Inspecting Committee in their reports in 1861 and 1862. These reports, together with a letter from the Irish Coast Guard and a report by Captain E.F. Roberts, Marine Inspector for the Ballast Board, were sent for approval to the Ballast Board, the Board of Trade and Trinity House, London. The Elder Brethren of the Ballast Board deferred making a decision on the lighthouse until they had the opportunity to inspect the site in early 1863. The inspection was carried out on the 9th of June, 1863, whereupon it was decided that the ideal site for the lighthouse was adjacent to the Alexander Nimmo (1783-1832)-designed Blacksod Pier. The lighthouse was officially sanctioned by the Board of Trade and Trinity House the following month.

A plot of one statute acre of ground was obtained from the Reverend Sir William Palmer (1803-85) at a rate of £1 per annum. As the proprietor of the nearby Altmore Quarries, Palmer was also well placed to offer the Board a ready supply of good quality granite at a cost of £100. Requests for tenders for the construction of the lighthouse prompted four responses, opened and evaluated by the Ballast Board in June 1864, with the contract being awarded to Bryan Carey’s tender for £2,100. Work appears to have begun in early autumn as the first payment was made to Carey in October. Progress on the lighthouse was almost disrupted by Palmer who, having agreed the lease of his land, objected in August 1864 to its construction due to the perceived impediment on the delivery of granite from his quarries to Blacksod Pier.

The summer of 1865 saw Carey complete his contract and, satisfied with his work, the Inspecting Committee noted that the tower was now ready for its lantern. Requests for tenders for the lantern brought two responses and two identical quotes of £340. A draw saw Chance Brothers of Smethwick, Birmingham, emerge as the successful tenderer. A Notice to Mariners, published in March 1866, stated that a fixed light showing red and white would be exhibited on the night of the 30th of June, 1866.

As a weather station Blacksod Point Lighthouse also proved invaluable during the Second World War (1939-45). Despite its neutrality during “The Emergency” (1939-46), Ireland continued to supply Great Britain with meteorological reports under an agreement dating back to its Independence. Unaware that 1,213 warships, 4,126 landing craft, 11,000 aircraft and 156,000 Allied troops awaited deployment in the English Channel, Edward “Ted” Sweeney (1906-2001), stationed at Blacksod since 1933, issued his customary weather observation report in the early hours of Saturday the 3rd of June, 1944. It forecast an approaching Force 6 storm. The report was forwarded to Southwick House, outside Portsmouth, where Group Captain James Stagg (1900-75), Chief Meteorologist for the Normandy Landings, took great interest in its detail.

Years of planning for the Allied invasion of Normandy hinged on one unpredictable factor: the weather. D-Day was originally planned for Monday the 5th of June, 1944, as air and tidal conditions were seen as conducive to landings by boat and plane. In a recent interview Sweeney’s widow, Maureen Sweeney, recalled that in the morning following her husband’s report a call came through to the post office where she worked asking for Ted to repeat his observations. An hour later, the same caller, ‘a lady with an English accent’, asked for the latest weather observations. Ted’s hourly reports, coupled with observations from a range of weather stations across Great Britain and Ireland, indicated that a weather system bringing strong winds, low cloud coverage and heavy rain would affect the English Channel on the 5th of June. At midday on Sunday the 4th of June, however, Ted reported a break in the weather with high cloud coverage and good visibility across land and sea. At a meeting with General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969), Stagg advised that this break was sufficient for the invasion to proceed. According to legend, at the conclusion of the meeting the clouds above Southwick House began to disperse: Ted Sweeney’s break in the weather had reached the English Channel. The D-Day Landings of Tuesday the 6th of June, 1944, the largest seaborne invasion in history, contributed to the Allied victory in the war. Today a plaque unveiled in 2004 commemorates the “D-Day Weather Forecast sent from Blacksod 4th June 1944″.

The National Inventory of Architectural Heritage would like to thank Barry Phelan and Mark Purdy of the Commissioners of Irish Lights for their kind assistance with this Building of the Month

Back to Building of the Month Archive