Building of the Month - June 2010

Dromana Gate, DROMANA Td., County Waterford

A history of Dromana Gate, near Cappoquin, County Waterford, which has been described as ‘one of the strangest gate lodges in the country’

A history of Dromana Gate, near Cappoquin, County Waterford, which has been described as ‘one of the strangest gate lodges in the country’

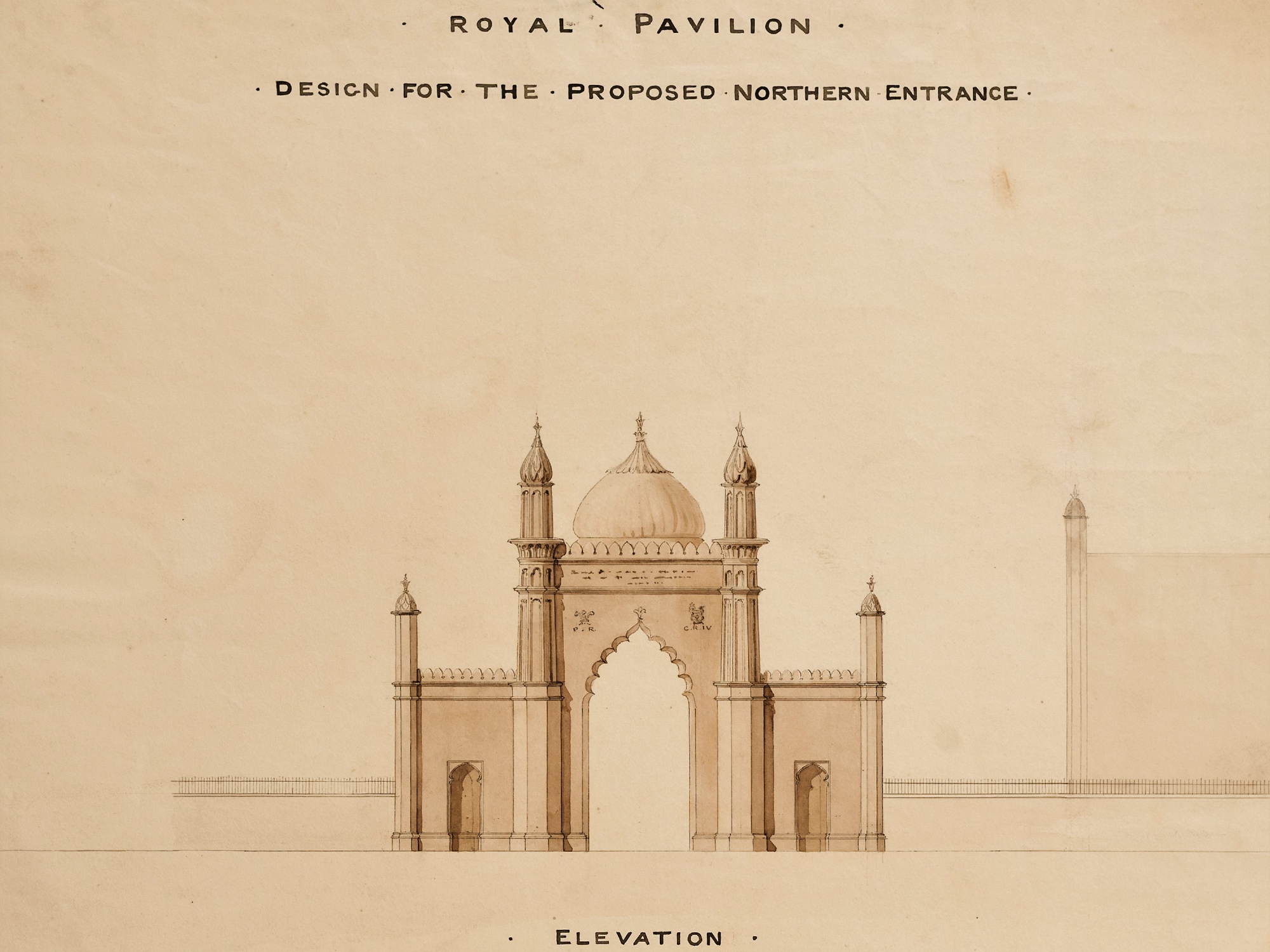

The origins of Dromana Gate on the periphery of Dromana Forest, near Cappoquin, County Waterford, are traditionally believed to date back to a papiér maché-detailed canvas-covered timber structure erected (1826) by the tenants of Villierstown to welcome home the newly-wed Henry Villiers-Stuart (1803-74) and Theresia Pauline Ott (d. 1867). It is said that the Villiers-Stuarts spent at least some of their honeymoon in Brighton, on the south coast of England, and that the gate was intended to bring back fond memories of the John Nash (1752-1832)-designed Royal Pavilion (1815-22), the centrepiece of that emerging seaside destination, a multi-domed extravaganza in the Indo-Saracenic style. The Royal Pavilion, a retreat for King George IV (1752-1835), then Prince Regent, represented a radical and very public departure from the cheerless Classicism monopolising the mainstream taste and exploited, on the exterior, almost every conceivable motif derived from Indo-Islamic and Mughal architecture and, in the State Apartments, fanciful decorative themes melding Chinese and Indian patterns.

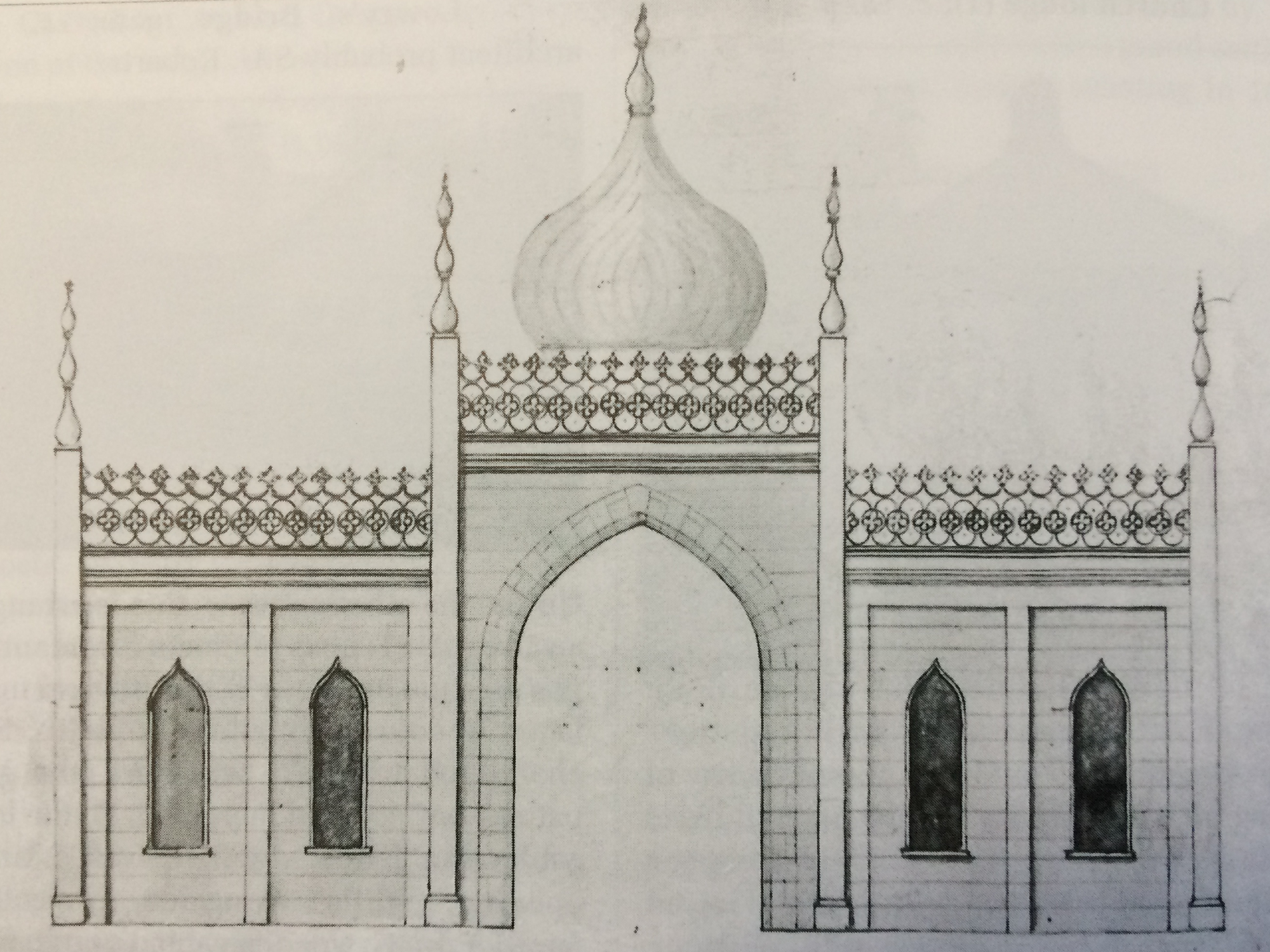

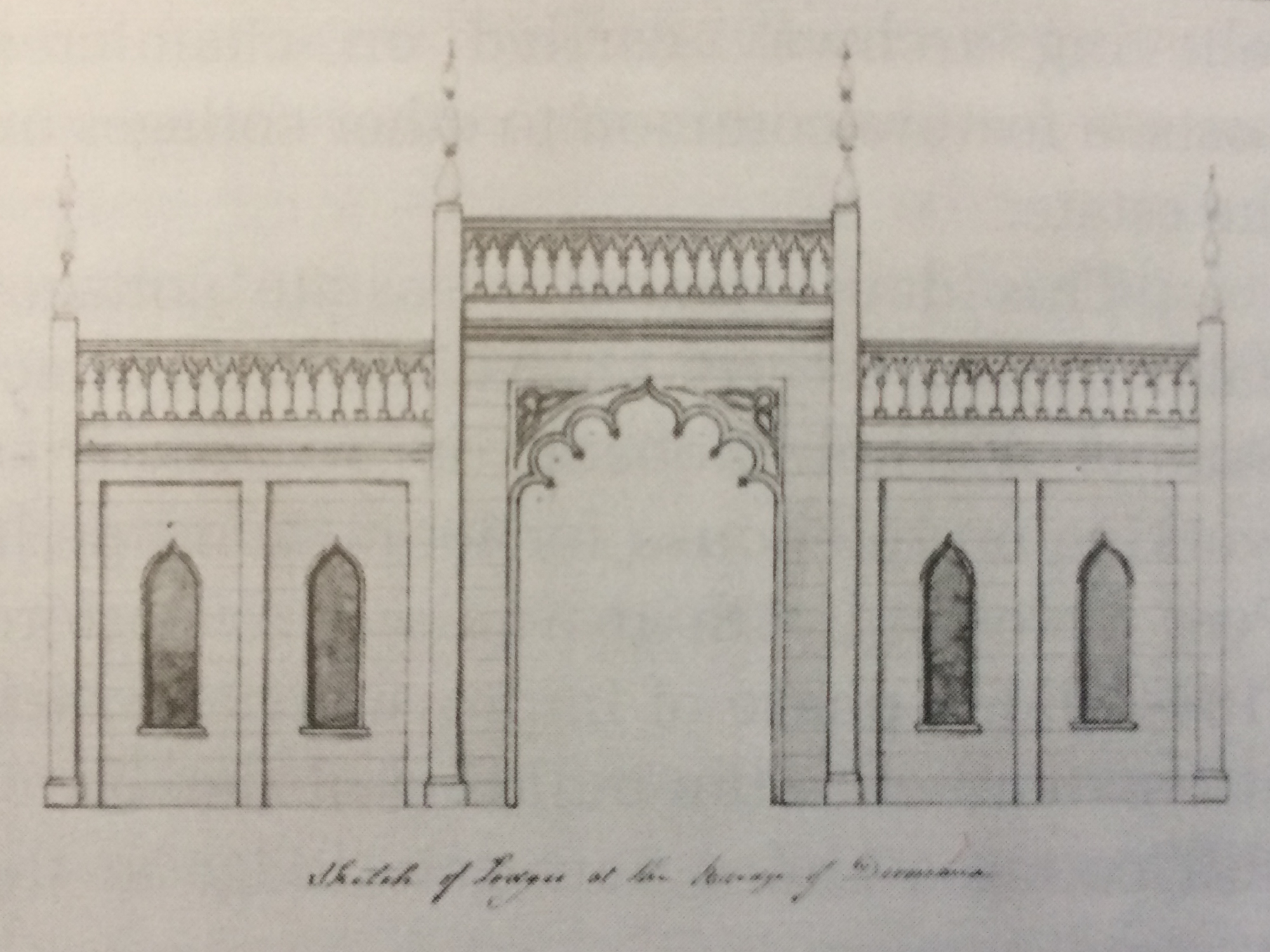

Surviving drawings for Dromana Gate are signed and dated (September 1849) by Martin Day (d. 1861) of Gallagh, County Wexford, who is best remembered today for his collaborations with Daniel Robertson (d. 1849) on a series of country houses in that county (figs. 2-3). Day appears to have been the architect of choice for the Villiers-Stuarts and his earliest drawings illustrate a portico for the ongoing “improvement” of Dromana House and a range of “offices” (1822) commissioned by the trustees of the estate of Lady Gertrude Amelia Mason-Villiers (d. 1809) acting on behalf of the young Henry who had not yet come of age. A later drawing (1836) shows an unexecuted proposal for a Classical gateway while further additions and alterations were made to the house and stables between 1843 and 1849, after which, according to the surviving drawings, Day began work on Dromana Gate. The Georgian substance of Dromana House having been lost in 1966, when the house was reduced back to its eighteenth-century core, Dromana Gate survives as Martin Day’s enduring contribution to the estate.

Original drawings are a valuable source of information on dates of construction and the identities of architects and clients, but, in the case of Dromana Gate, the drawings seem to pose more questions than they answer. If the tale of the honeymoon gift is true – and it may well be only a tale – it is not recorded what prompted Villiers-Stuart to commission a permanent replacement over two decades later. A gate with a similar plan is named as Cappoquin Gate Lodge on the first Ordnance Survey (1843) and it has been suggested that Day’s drawings are merely a visual record of that structure, however, an alternative scheme, also dated September 1849, is evidence that Villiers-Stuart was being presented with options to choose from and that the design process was then still in flux (fig. 3).

The Brighton connection must also be considered and, on stylistic grounds, the inspiration, if any, seems not to have come from the Royal Pavilion but from the so-called “North Gate” designed (1832) by Joseph Henry Good (1775-1857) (fig. 4). We do not know if the Villiers-Stuarts revisited the scene of their honeymoon or if, indeed, Day made a journey there, but the similarity between the designs for the two gates seems to be too great to be entirely coincidental. Both can be viewed as part of a groundswell of interest in the “exotic” brought about by such publications as the lavishly-illustrated multi-volume Oriental Scenery (1795-1808) by Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and his nephew William Daniell (1769-1837). A talented architect might introduce motifs from the equally-popular Gothic Revival style to produce a dream-like design transplanted from a far-away, near-mythical land.

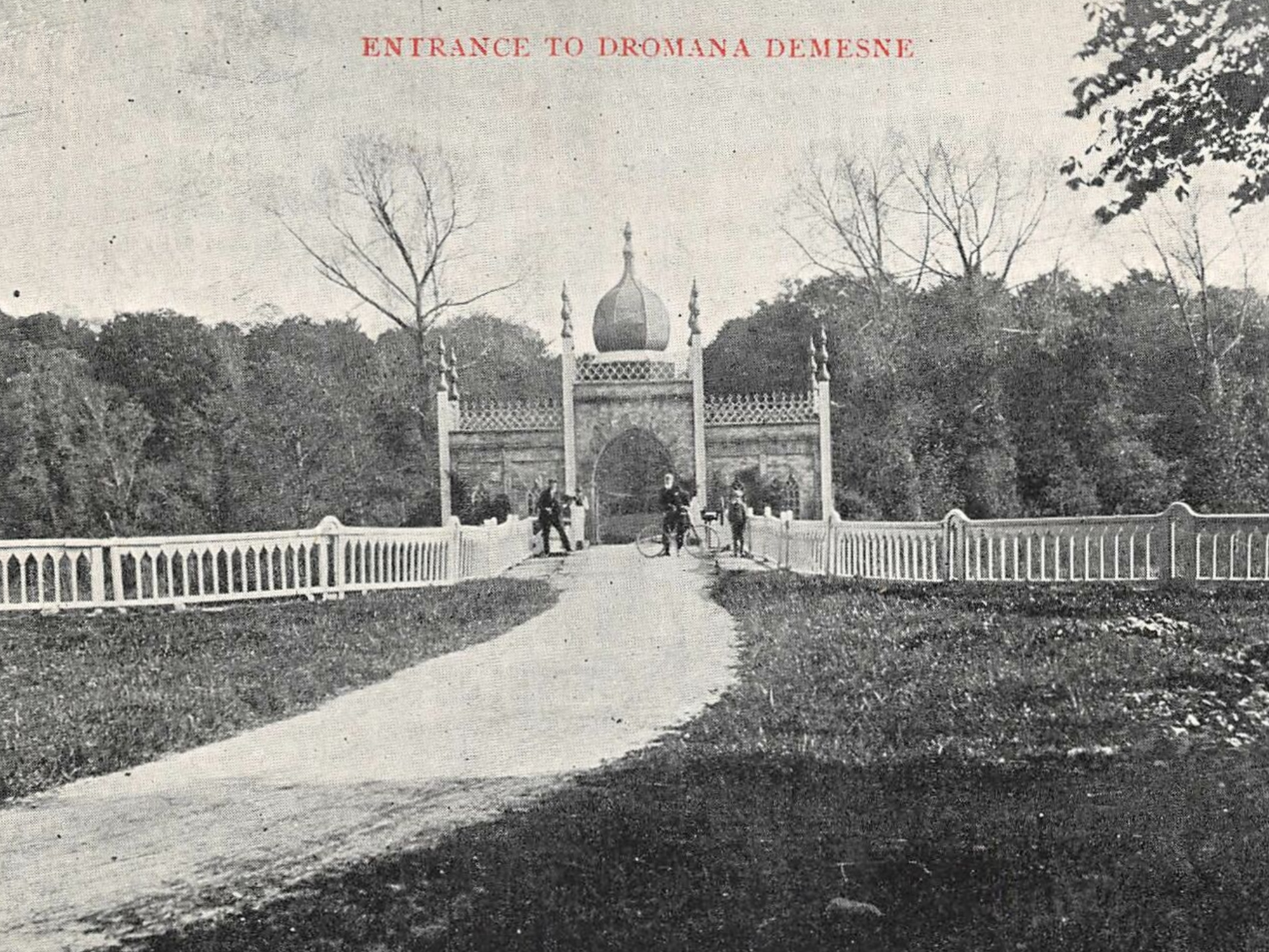

Dromana Gate presents two perfectly symmetrical façades with one greeting the visitor on the approach road over the Finisk River and an identical one bidding them farewell as they leave the estate (fig. 5). The central carriageway, a boldly rusticated pointed arch, has its roots in the medieval Gothic but is placed beneath a copper-covered onion dome evocative of the Indian subcontinent. Coupled ogee-headed windows on either side, each one set within its own shallow rectangular recess, may have been familiar to the casual observer through their appearance in contemporary Georgian Gothic churches. All corners are finished with slender piers, those around the carriageway soaring over those around the lodges, the bulbous three-tiered minarets at their summits bringing to mind the ancient mosques of the Middle East. A wrought iron parapet reintroduces the Gothic theme with its dazzling display of overlapping quatrefoils; each overlap is filled with a smaller quatrefoil. All of these details are set against finely-cut flecked sandstone walls which appear to transform in palette according to the changing of the seasons, giving off a golden glow in the late summer sunshine, a silvery sheen on the coldest of winter days.

The strict symmetry of the façades is continued beneath the vaulted carriageway where false doors flank the entrances to each lodge. The accommodation, now stripped of all plasterwork and timber, was basic but functional with one vaulted lodge serving as a kitchen-cum-parlour and its opposite number serving as a bedroom.

Dromana Gate has been described as the best surviving example of the so-called “Hindu-Gothic” style in Ireland – Turkish baths in Dublin that might once have competed for the title have long since been demolished – but this unique claim has not necessarily guaranteed its survival. Restored (1967-9) by the Irish Georgian Society, James Howley later remarked that ‘remote follies or garden buildings will always be subject to vandalism [and the society] has learned this to its cost’, and a further restoration by Waterford County Council was required in 1990 to make good the damage caused by trespassers.

Damian Murphy, Architectural Heritage Officer, National Inventory of Architectural Heritage

Back to Building of the Month Archive